Hello anyone, everyone, my name is Really Kinda Sad Right Now, because today I want to talk about a game I have long considered among my favorites of all time: Playdead’s seminal puzzle platformer Limbo.

Limbo was released in 2010, alongside other visually striking, mechanically interesting indie platformers Super Meat Boy and VVVVVV. This had a profound impact on me as a player; ever since, those have been my favorite types of games, and I have pretentiously proclaimed such at every opportunity.

As a result, I was hype af for the release of Playdead’s follow up, Inside, six years later. I bought it, got stuck about four minutes in, and then gave up for literally years.

It was pretty pathetic.

And I have thought about this pretty pathetic thing every four to six months since, but never really felt the impetus to do something about it until the release of the official Kotaku review of New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe a few weeks back, which came from the mind of Tim Rogers.

Rogers has been my favorite games critic since 2013, when Brendan Koegh, the author of the Spec Ops: The Line – five stars – critical analysis Killing Is Harmless – 4.5 stars pointed me to Rogers’ 18,000-word, not-very-positive review of Bioshock Infinite – 4 Stars.

He and I don’t always agree, for example Bioshock Infinite. Also, The Last of Us – two stars. Yeah. That’s right. The Last of Us, a really interesting movie with a stellar opening but otherwise underwhelming interactive experience tacked on.

Oddly enough, my specific gripes are not entirely unlike the ones Rogers has with Infinite, though in a way that is much, much more specific and irritating to other people.

I have incredible respect for Tim Rogers’ opinions. When it comes to a discussion about gamefeel and the fundamentals of functional mechanics, I genuinely don’t think there is anyone who games criticisms better. So, I was heartbroken when, about three quarters of the way through that review, he called out Limbo. In the text version, it’s an off-hand remark. In the video itself, he briefly pauses to say he literally hates it and also spoils the ending, kind of.

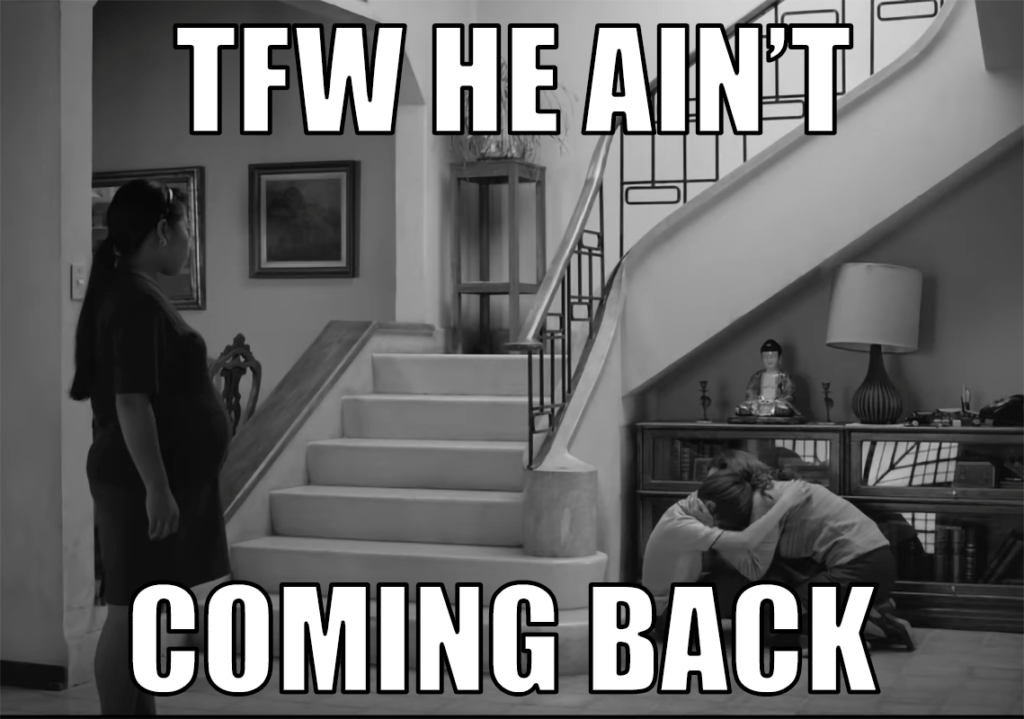

My initial response was shock and revulsion followed by depression, anger, rejection, and then a little bit of curiosity. It had been so long since I played Limbo that… maybe I was wrong. But before I could really think about that, it was time to finally freaking finish Inside.

So, I picked up another copy that I could more easily play from my couch (i.e. not on PC) and sat down with it. I did not move until the credits rolled. It was a work night. Oops.

But I was a changed man.

I immediately figured out that thing I was stuck on all those years ago, got mad at myself retroactively – as I am wont to do, and then never stopped again. I was genuinely blown away. Despite having even less text than Limbo (there’s no button prompt to start the game), it tells a cohesive and coherent narrative that digs into themes of humanity and control: a kid who freed himself from zombification escapes at first towards freedom but ultimately back to the people who believed they owned him.

It goes to some seriously unexpected places, with the last thirty minutes in particular being some of the most genuinely bonkers I’ve ever played in a game that didn’t appear at first glance to be completely bonkers.

Really, it’s amazing.

A few days later, I booted up Limbo. Fully expecting to love it every bit as much as I did back in 2010.

I… didn’t.

I still liked it, of course, or so I keep telling myself. But playing it after Inside – and with Tim Rogers’ entire En Es Em Be You Dee review in mind – is kinda rough.

At times, Limbo is reminiscent of the rage-classic I Wanna Be the Guy without the meta-hilarity.

I subscribe to the theory of game design that a preternaturally good player should be able to reach the credits of a game on their first try without dying once. If the logic and rules are consistently applied, someone with a flawless grasp of the mechanics will be able to make it through. I Wanna Be the Guy quote-unquote subverts your expectations right from the start by changing the way that apples “fall” – both based on the rules of the game as you think they have been set out in the opening moments and the world in general, since apples don’t typically fall up. But that’s the point. That’s the whole game. And I respect its commitment to making you angry at every moment – the sweeter the feeling of accomplishment when you finally pass an obstacle, or so some might have you believe.

That isn’t Limbo’s shtick, though. The completion of a puzzle tends to come not with a sense of pride but relief.

I can pinpoint the moment where my devotion to Limbo started to waver: you are running underneath some heavy machinery – two identical contraptions. There are triggers on the floor. Step on the wrong spot, and you will be crushed. There is no indication that this is the case until it comes down upon you, though you can reasonably guess it from the presentation.

As someone who has played a video game before, you would expect that you have to jump over the low-ground onto the center high-ground. And for the first, you would be right. Jump, land on the higher platform, and you’re set.

The second one, though, landing on the center triggers the machine.

If you think about intent, this makes sense. A general platformer putting two of the same jump in a row, particularly one with such serious consequences, would be par for the course, but not this particular puzzle platformer.

But that thought requires you to be constantly outside of the game experience, trying to read the developer’s minds instead of the actual experience they built.

Your player sense tingles, you jump to the center a second time, and you die. And then you groan or shout at the screen and do it again, correctly. But you know from then on, if you hadn’t known already, that this game hates you.

If you want to be kind in return, maybe chalk this up to narrative: it is, after all, limbo – literally; it’s confusing and disorienting. You can’t get out of limbo by following “rules.” You do so by getting into philosophical discussions with very smart mostly Greeks as part of your epic quest to woo a girl you’ve been obsessed with since you were a child even though you only met her twice and she married someone else, so, like, get over it, dude.

Do you remember that God of War-like Dante’s Inferno game? I don’t know if it’s possible to miss the point harder than that thing did. Although maybe I just came close.

Anyways.

You spend a lot of time waiting in Limbo. About a third of that is waiting for something so you can proceed – most of that on this one fucking puzzle, but generally this is about elevators and elevator-likes; another third is waiting for the game to kill you because you didn’t realize you needed to do one thing before triggering another and welp, it’s too late now.

The third… third is a hybrid, where you are redoing one of those initial waiting periods because you didn’t realize there was something in the puzzle ready to kill you until you finally saw the exit and a big heavy ball from a minute ago lands on your head, at which point you realize the puzzle was actually just about avoiding the ball the whole time. And how could you have known? Even if it didn’t hit you, that was almost certainly not because you knew it was coming but that you just happened to follow the necessary pattern.

And all this results in the crushing realization that the design philosophy behind Limbo is… bad.

And Playdead must have realized it, because nothing that I just said applies to Inside. Inside is damn near perfect, taking everything that worked in Limbo and wildly improving everything else.

Still, I find it impossible to take the final, logical step and just say that Limbo is not, in the year CE Two Thousand Nineteen, a good game. That the love for it is not only misplaced now but may have been misplaced from the start.

I can’t do that because it was so significant to me for so long, that it helped to change the way I think about games and what I look for in games. How do you accept that you don’t like a thing that mattered that much? It still has its moments! All these years later, individual moments are as intense and powerful as they ever were… but so what? When I actually had trouble keeping going in between those, because there were other things I could have been doing and would rather have been doing?

Ugh.

Ya know, I thought a lot about the title for this video. Back when I conceived of it as a review of Inside after my wildly positive reaction to that, or maybe a look at the evolution of Playdead’s style. I knew they would be different but believed them equivalent. That this video might be about how they’re both perfect. Then it became about how they were perfect in, ya know, their own way.

And then one wasn’t perfect anymore.

Six Point Zero out of Ten